America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2018

America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (AWIA) is a federal law that provides for water infrastructure improvements throughout the country. AWIA became law on October 23, 2018. Section 2013 of AWIA includes newly enacted requirements for community water systems serving more than 3,300 people.

The Wide-Ranging Role of GIS

Chances are your perception of GIS – or Geographic Information Systems – is that it is a simple, computer-based mapping system. While that is true, it is not the whole story. Its utility and versatility extend well beyond this functionality. Communities are beginning to leverage GIS to keep an inventory of public asset information via its mapping interface. Further demand for GIS solutions is growing, as it has become an integral tool for managing information and establishing a data-driven basis for intelligent planning and decision-making. The organizational and analytical capabilities of GIS can help communities work more efficiently and make well-informed operational and planning

Autonomous Vehicles: The Transportation Planning Evolution is Upon Us

Technology is evolving rapidly, and will have profound effects on our transportation options, networks, and spending habits within the next few decades. Public officials need to start preparing today for an inevitable, vastly different infrastructure future due to a variety of technologies that are emerging and changing the ways we plan and develop our future roads, parking, transportation networks, and Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS).

Monitoring Manganese Levels in Drinking Water is Vital for Community Well-being

Increased levels of manganese in drinking water supplies have raised concern in some communities and increased speculation that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will make regulation changes. Manganese is a naturally occurring element found in groundwater, very acidic soil, and foods such as seeds, grains, nuts, legumes, green leafy vegetables, and in drinking water.

Tips on Effectively Securing and Managing Grant Funds for Projects

Obtaining grant funds for various projects is paramount for most communities; however, securing and managing these funds for critical projects is no simple task. In an ideal world, effective Capital Improvement Planning allocates funding for improvements; however, when accidents occur or Mother Nature strikes, disaster recovery efforts can be a significant funding challenge for communities. Grant funding knowledge is essential to ensure that a community can recover from disaster and prevent future loss of life and property.

Lead Service Line Replacements – Top Considerations

Lead water mains have become a significant concern nationwide as stories have made headlines warning of high concentrations of lead in drinking water. Understanding the complexities for replacing lead services lines (LSL) in a community can seem daunting. Often community leaders and stakeholders don’t understand their options for implementing an LSL replacement plan.

Utility Damage Prevention: The Growing Role of Broadband

The infrastructure that utilities build and maintain can run the spectrum from convenience for the utility’s customers to critical infrastructure (both for customers and national grids.) The potential damage to the many components of that infrastructure can come from different sources with varying intent.

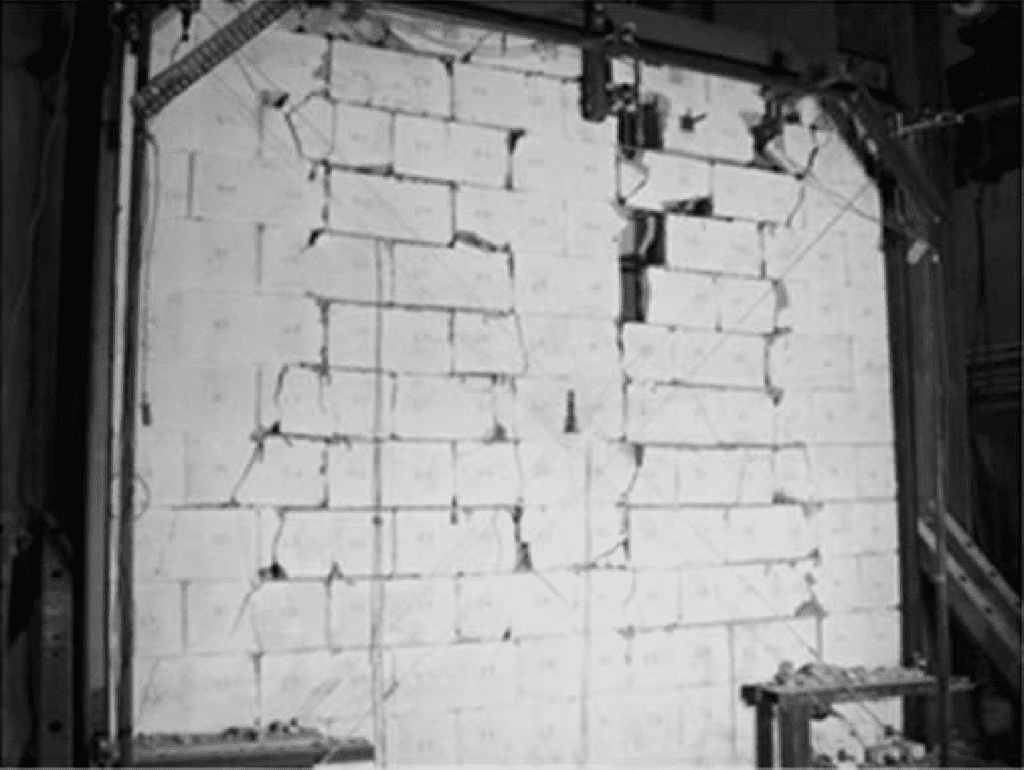

Masonry Shear Walls – Joint Reinforcement as Primary Shear Reinforcement

Partially grouted masonry shear walls are common in North America. Construction of partially grouted concrete masonry shear walls can benefit greatly by placement of joint reinforcement in bed joints of each or every other course instead of deformed reinforcement in bond beams, because placement and grouting of bond beams slow construction. Joint reinforcement is already used to help control cracking and provide prescriptive horizontal reinforcement. With sufficient area and ductility of wire, joint reinforcement can also provide the tension capacity to span across cracks in shear walls and to act as primary shear reinforcement for in-plane shear forces.

Learn How the Illinois Accessibility Code Changes Can Affect Your Community and Code Officials

Now that the Illinois Accessibility Code (IAC) has been updated for the first time since 1997, it is crucial that your community’s Code Officials, Building Inspectors and Plan Reviewers become knowledgeable about some key changes. The IAC requires certain accessibility standards to guarantee that newly-constructed or renovated buildings are safe and readily accessible to persons with disabilities. Some of these standard have been updated in 2018, and this article highlights the major changes.

Top Changes to the Illinois Accessibility Code – 2018 Update

The Illinois Accessibility Code (IAC) has been updated for the first time in nearly 20 years, and went into effect on October 23, 2018. Established in 1997, the IAC requires certain accessibility standards to guarantee that newly-constructed or renovated buildings are safe and readily accessible to persons with disabilities. This article lists some of the major observations and changes that we noticed.